The world is not flat anymore

Why international growth has entered a new regime

And why this is good news for those who know how to read it

For nearly two decades, business leaders, founders, investors and consultants have operated under a powerful mental model: the idea that the world had become flat. That geography mattered less. That borders were friction, not structure. That once you had the right product, the right technology and the right growth playbook, expanding internationally was largely a matter of execution speed and capital allocation. You entered new countries the way you opened new tabs in a browser. Different language perhaps, different currency sometimes, but fundamentally the same game.

Today, that metaphor breaks the moment it touches reality. When a single executive order can alter “reciprocal” tariff rates, and then be modified again within the same year; when tariff suspensions, retaliatory lists, and trade investigations become moving parts rather than background conditions; when cross-border data transfers are treated less like a neutral technical flow and more like a permissioned corridor; when export controls redefine what you can ship, where you can manufacture, and with whom you can collaborate; and when “digital sovereignty” is no longer a slogan but a policy agenda with its own timelines and enforcement logic, you are no longer operating on a flat playing field. You are operating on a terrain shaped by regimes, incentives, and local power structures.

That idea is no longer operational. Not because globalization is over, borders are closed or international business has become impossible; but because the assumptions that made the so-called flat world navigable have collapsed. What we are experiencing is not a reversal into isolation, nor a nostalgic return to protectionism. It is a change of regime. A shift from a world optimized for scale through standardization to a world organized around context, asymmetry and local legitimacy. The terrain has not disappeared. It has become uneven again, and pretending otherwise has become a strategic risk.

For founders and scale-up leaders, particularly in Europe, this shift is not theoretical. It shows up in failed market entries, stalled growth curves, regulatory dead ends, cultural misunderstandings, sales cycles that behave nothing like the home market, and products that technically work but never truly land. The playbooks that once felt universal now travel poorly. The promise of frictionless expansion has given way to a reality of layered constraints that cannot be abstracted away.

I have been building, launching and scaling businesses across borders for more than twenty five years. Long before international expansion became a slide in a pitch deck, it was a messy, human, deeply contextual practice. What struck me early on is that what looked like simplicity was often the result of invisible alignment rather than inherent universality. When that alignment disappears, complexity re-emerges. Today, that complexity is no longer hidden. It is structural, visible and increasingly decisive.

The end of the flat world narrative does not call for retreat. It calls for maturity. It requires abandoning the comforting illusion that one go-to-market strategy can be copied and pasted across geographies, and replacing it with a more demanding but far more powerful approach: a Local-first global strategy. One that treats culture, regulation and local market logic not as constraints to be minimized, but as sources of competitive advantage when properly understood and integrated.

To understand why this shift matters, and why it feels so disruptive to many organizations, it is worth revisiting where the flat world idea came from, what it captured accurately, and where its limits have always been.

The flat world, revisited

In 2005, journalist and author Thomas L. Friedman published The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. The book became a global reference almost instantly, not because it was academically radical, but because it articulated with remarkable clarity what many business leaders were experiencing at the time. Friedman argued that a combination of technological, economic and political forces had flattened the global competitive landscape, enabling individuals and companies from almost anywhere to compete and collaborate in ways previously impossible.

At the core of Friedman’s thesis were what he famously called the “flatteners”: the fall of the Berlin Wall, the rise of the internet, the standardization of software platforms, the explosion of outsourcing and offshoring, and the emergence of global supply chains coordinated in real time. In his words, “the world is being flattened by the convergence of the personal computer, the fiber-optic cable, and the rise of workflow software.” This convergence, he argued, created a new phase of globalization in which geography mattered less than connectivity, and where competitive advantage could be generated from almost anywhere.

Friedman was not naïve about differences between countries, but his argument suggested that these differences were becoming increasingly secondary to access and capability. As he put it, “Globalization 3.0 is shrinking the world from a size medium to a size small and flattening the playing field at the same time.” For a generation of executives, this idea translated into a simple operational belief: if the playing field is flat, then scale and speed win. You optimize centrally, deploy globally, and let efficiency do the rest.

This narrative captured something very real. There was indeed a historical window, roughly from the late 1990s to the mid 2010s, during which global integration accelerated faster than institutional or cultural fragmentation. Capital flowed freely, supply chains stretched across continents, digital platforms imposed de facto standards, and English became the default operating language of global business. For companies positioned at the right place in this system, the world did feel flatter. Not uniform, but navigable. Not frictionless, but predictable enough to abstract.

Yet even at the height of its influence, the flat world thesis rested on a partial view of reality. It described the world as seen from the vantage point of those who already had access to capital, infrastructure, education and global networks. The flattening was uneven, and the benefits were asymmetrically distributed. Cultural depth, regulatory sovereignty, political power and local market structure never disappeared. They were temporarily overshadowed by the dominant logic of efficiency and scale.

What has changed today is not that these dimensions suddenly matter again. It is that they can no longer be ignored without consequence. The flatteners have not vanished, but they no longer override everything else. Technology connects, but it also fragments. Regulation harmonizes in some areas and diverges sharply in others. Geopolitics reasserts itself not as noise, but as structure. Culture, long treated as a soft variable, becomes a hard constraint when products, narratives and trust mechanisms fail to translate.

In retrospect, the flat world was less a permanent state than a moment of alignment between technology, economics and politics. A moment in which the cost of ignoring local reality was low enough to be absorbed by growth. That moment has passed. The world has not become closed. It has become differentiated again, and the differentiation is now where strategy begins.

Understanding this is not an academic exercise. It is the difference between expanding internationally and actually becoming local. Between exporting a model and building a presence. Between being perceived as an external player and operating as a legitimate actor within a market. The next phase of global business will not be won by those who deny fragmentation, but by those who know how to work with it intelligently.

This is where the real work starts.

Re-fragmentation is not chaos. It is structure returning.

When leaders talk about today’s international environment, the dominant vocabulary is often defensive: fragmentation, uncertainty, volatility, risk. The implicit message is that something has been lost, that a simpler era has ended and that global growth has become inherently more fragile. This framing is understandable, but it is also misleading. What we are witnessing is not the collapse of order. It is the return of structure.

The so-called flat world reduced complexity by compressing it. It allowed companies to postpone hard questions about culture, regulation, legitimacy and local power dynamics because the cost of postponement was temporarily low. Digital distribution scaled faster than institutions could react. Capital moved faster than regulation. Products traveled faster than meaning. For a time, speed compensated for depth.

That time is over, but the alternative is not paralysis. It is precision.

Re-fragmentation does not mean that everything is different everywhere. It means that differences matter again, and that ignoring them is no longer neutral. This is an important distinction. A fragmented world is not a hostile world. It is a world that rewards those who understand how markets actually function from the inside, rather than from a spreadsheet.

The first mistake many organizations make when facing this reality is to treat fragmentation as a macro phenomenon only. They look at geopolitics, trade wars, tariffs, sanctions, and assume that the game has become political before it became operational. In practice, the opposite is often true. The most decisive frictions are not at the level of states, but at the level of everyday business interactions. They show up in how decisions are made, how trust is built, how risk is perceived, how disagreement is expressed, and how authority is recognized.

This is where culture moves from a background variable to a primary driver of outcomes.

Culture moves from background to operating system

One of the most useful lenses to understand this shift comes from Erin Meyer and her work The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business. Meyer’s central contribution is deceptively simple: culture does not disappear in global business; it becomes invisible to those who assume their own norms are universal. The problem is not cultural difference itself, but the illusion of similarity.

In a world that felt flat, many teams operated under the assumption that professional behavior converged naturally. Meetings, feedback, decision-making and leadership styles were expected to align around a shared global norm, usually implicit and often Anglo-American in origin. When misalignment occurred, it was attributed to execution issues, individual performance or market immaturity.

What Meyer demonstrates, and what years of operational experience confirm, is that these misalignments are systematic. They follow patterns. Communication can be low-context or high-context. Authority can be hierarchical or consensual. Trust can be task-based or relationship-based. None of these dimensions are better or worse in absolute terms, but each of them shapes how business actually gets done. Ignoring them does not make them go away. It simply shifts their impact downstream, where it becomes more expensive to correct.

I worked with a Nordic company in digital advertising technology, providing online monetization platforms for TV broadcasters. The team at headquarters was exceptionally strong: highly analytical, bold in their decisions, pragmatic, and relentlessly action-driven. Their assumption was simple and logical: if the product delivered value and the economics made sense, adoption would follow.

When they expanded into what they perceived as culturally close European markets, results diverged sharply. In one country, deals progressed smoothly. In another, discussions were positive but nothing closed. The issue was neither the product nor the people. It was decision dynamics. At HQ, decisions were made quickly, explicitly, and owned by clearly identified leaders. In the target market, decisions emerged slowly, through alignment across multiple stakeholders, often outside formal meetings. Once the company adjusted its engagement model to reflect that reality, without changing its ambition or standards, momentum returned almost immediately.

What unlocked growth was not a change in strategy, but a shift in how decisiveness itself needed to be expressed locally.

In the flat world narrative, culture was often treated as an adaptation layer to be handled after market entry. You launch first, then localize. In a re-fragmented world, culture is part of market entry itself. It determines whether your value proposition is understood as credible or intrusive, whether your product is seen as empowering or irrelevant, whether your brand feels legitimate or foreign.

This is not a call to over-customize or to lose strategic coherence. It is a call to recognize that global strategy is no longer about deploying sameness efficiently, but about orchestrating difference intelligently. The most successful international organizations today are not those that look identical everywhere, but those that feel local while remaining structurally coherent.

Regulation is no longer downstream. It is upstream.

Regulation reinforces this dynamic rather than replacing it. Regulatory environments increasingly encode cultural and political priorities into hard constraints. Data protection, competition law, labor regulation and AI governance are not neutral technical layers. They reflect societal choices about privacy, power, fairness and accountability. Treating regulation as a hurdle to clear rather than a system to understand is one of the fastest ways to misread a market.

Importantly, this does not mean that every country requires a bespoke strategy built from scratch. What it means is that expansion now requires a different sequence. Instead of asking “How do we deploy our model here?”, the more productive question becomes “How does this market actually work, and how does our model need to be translated to operate credibly within it?”

A similar pattern appeared in the online payment space, where regulation and trust are inseparable. A fast-growing payment platform entered a new European market with a strong technical offering and solid early traction. From a compliance standpoint, everything was formally in place. Yet key commercial partnerships failed to activate at scale.

The underlying issue was not regulatory risk, but perception of responsibility. In this market, regulation functioned as a trust architecture. Partners expected visible signals of long-term commitment, governance maturity and shared accountability. Once the company reframed its market posture accordingly, not by slowing down innovation but by making trust explicit, discussions shifted. Regulation had not constrained growth; misunderstanding its role in the ecosystem had delayed credibility.

In regulated markets, trust is not assumed from compliance; it is inferred from how responsibility is demonstrated over time.

This shift in sequencing replaces anxiety with agency. It reframes fragmentation not as an external threat, but as an internal capability gap that can be closed.

Geopolitics becomes operating context, not headline risk

The world did not suddenly become political. It became explicit about what was always true: markets sit inside political systems, and political systems defend interests. This does not mean business leaders must become political actors. It means they must become politically literate. They must understand which partnerships create dependency, which supply chains are fragile, which technologies are sensitive, and which narratives are viable.

The provocative truth is that geopolitics is not only about conflict; it is about leverage. Export controls, sanctions, strategic subsidies, investment screening, and reciprocal tariffs are tools of economic power. They shape what can be built, where it can be sold, and how value can move across borders.

None of this ends global business. It changes its grammar. It encourages resilience, optionality, and stronger local anchoring. It also rewards those who can interpret these dynamics without overreacting, and translate them into choices that improve execution.

One GTM fits all is no longer a shortcut. It is a liability.

All of this leads to a fundamental reassessment of the dominant expansion model of the past two decades: the idea that one go-to-market strategy can be deployed everywhere with minor adjustments. In a flatter world, this approach felt efficient. Today, it is increasingly brittle.

The issue is not that standardization is inherently wrong. Coherence still matters. Scale still matters. What has changed is where standardization applies. The error lies in standardizing assumptions rather than structures. When companies assume that buyer behavior, trust dynamics, sales cycles and decision authority translate directly across markets, they are not being ambitious. They are being inattentive.

A go-to-market strategy is not just a set of channels and messages. It is an implicit theory of how value is recognized and converted into revenue in a specific environment. When that theory is imported without translation, friction accumulates quietly until it surfaces as underperformance. Deals stall. Partnerships fail to activate. Teams struggle to explain why traction remains elusive despite strong fundamentals.

In industrial and telecom environments, the limits of a one-size-fits-all go-to-market approach are even more visible. I worked with a provider offering mission-critical infrastructure for enterprise clients. In some countries, sales cycles were short and transactional. In others, they were long, cautious and deeply risk-driven, because the product directly impacted the client’s core operations.

The initial approach treated every market as a one-shot sale. It underperformed. We then reframed the model on both sides, shifting from a transactional mindset to an Industry-as-a-Service logic. The provider moved from selling equipment to delivering continuity, reliability and shared operational outcomes. Clients, in turn, moved from purchasing to partnering. This change did not simplify the offer. It made it intelligible in markets where trust is built over time rather than at signature.

What changed was not the ambition to grow, but the unit of value on which the relationship was built.

The alternative is not to reinvent everything market by market. The alternative is to separate what must remain global from what must become local. Product vision, brand coherence, core capabilities and learning systems can and should be orchestrated globally. But market entry, positioning, pricing logic, partnership models and sales motion need to be grounded locally to be credible.

This is where a local-first global strategy becomes not just a concept, but a practical operating model. It starts with the premise that international growth is not about projection, but about translation. You do not export a solution; you adapt a proposition to the way a market already solves problems. You do not impose a narrative; you align with existing frames of reference. Over time, this creates a form of legitimacy that no amount of marketing spend can buy.

Crucially, this approach reduces risk rather than increasing it. By engaging with local reality early, organizations surface constraints when they are still manageable. They build trust before scale amplifies mistakes. They learn faster, not because they move blindly, but because feedback is meaningful. Expansion becomes a series of informed commitments rather than a leap of faith.

The end of the flat world narrative does not signal the end of global ambition. It signals the end of global naivety. For leaders willing to engage with this shift thoughtfully, the opportunity is significant. Markets have not closed. They have become more explicit about their rules.

Those who learn to read those rules do not just survive re-fragmentation. They turn it into an advantage.

International Growth Fails Less From Strategy Than From Misreading the Operating System

Taken together, these situations all point to the same conclusion. International growth rarely fails because teams lack intelligence, ambition or execution capacity. It fails when strong models are projected into environments governed by different decision logics, trust mechanisms and risk perceptions. Culture shapes how authority and alignment work, regulation encodes what a market considers legitimate behavior, and go-to-market success depends on recognizing what form of commitment a client actually values. In a re-fragmented world, these elements are no longer background noise. They are the operating system. Organizations that learn to read and integrate them early do not become slower or more cautious. They become more precise. And precision, in international expansion, is what turns complexity into durable growth.

From global ambition to local power: a Local-first global strategy

At this point, one conclusion should be clear. International growth has not become a gamble. It has become a craft.

The mistake many leaders still make is to frame the current environment as a choice between two extremes: either remain global and risk being out of sync with local realities, or become local everywhere and lose coherence, scale and identity. This is a false dilemma. The organizations that succeed internationally today do not choose between global and local. They sequence them.

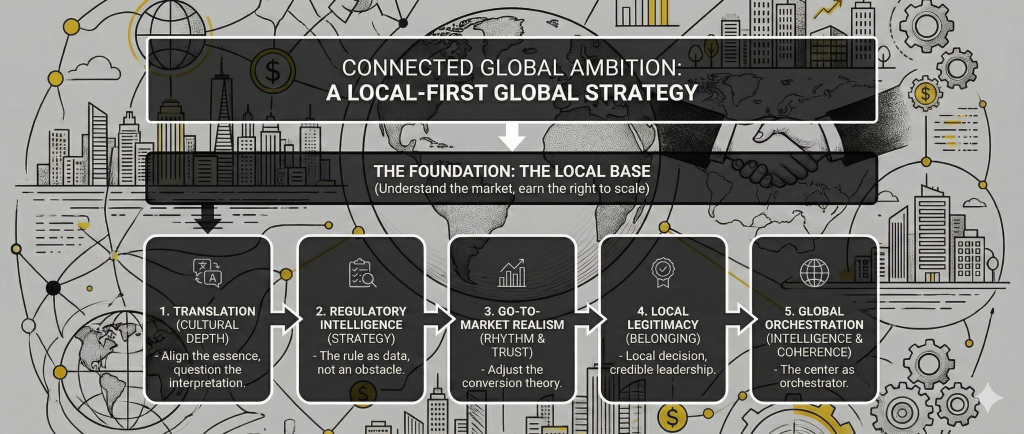

A Local-first global strategy starts with a simple but demanding premise: you do not earn the right to scale in a market by arriving with a strong model. You earn it by proving that you understand how that market actually works. Once that understanding is in place, scale becomes not only possible, but defensible.

This approach is neither improvised nor artisanal. It is structured. Over the years, across multiple countries, sectors and expansion phases, I have seen the same pattern repeat. When international growth works, it follows a recognisable architecture, even though its expression is always context-specific.

1) The first pillar is translation, not adaptation

Most companies believe they are adapting when they enter a new market. In reality, they are often localizing at the surface level while keeping their core assumptions intact. Translation goes deeper. It forces you to question how your value proposition is interpreted locally. What problem are you really solving here? Who is perceived as legitimate to solve it? What signals credibility, and what triggers distrust?

This is where cultural frameworks such as those articulated by Erin Meyer become operational rather than academic. Communication styles, decision-making norms, attitudes toward hierarchy and risk are not soft considerations. They directly shape how your product is evaluated, how your sales process unfolds, and how long trust takes to build. Translation means aligning your proposition with these realities without diluting its essence.

2) The second pillar is regulatory intelligence, not compliance

In a local-first strategy, regulation is not treated as an obstacle course to clear once the strategy is set. It is treated as part of the strategy itself. Regulatory frameworks tell you what a market protects, what it fears, and what it expects from those who want to operate within it.

Companies that integrate regulatory logic early tend to make better strategic choices. They choose different entry modes. They structure partnerships differently. They prioritize certain features over others. Most importantly, they avoid building momentum on foundations that will later be invalidated. This is not about being conservative. It is about being aligned.

3) The third pillar is go-to-market realism

A go-to-market strategy is not just a set of channels and messages. It is an implicit theory of how value is recognized and converted into revenue in a specific environment. When that theory is imported without translation, friction accumulates quietly until it surfaces as underperformance. Deals stall. Partnerships fail to activate. Teams struggle to explain why traction remains elusive despite strong fundamentals.

I have seen strong products fail to scale internationally not because they were misunderstood, but because they were introduced with the wrong rhythm. In one market, pushing for speed built confidence. In another, it triggered resistance. The same sales script produced opposite reactions. When the team stopped asking how to replicate their home-market success and started asking how trust is actually built locally, conversion followed. Nothing fundamental changed, except the sequence.

4) The fourth pillar is local legitimacy

There is a fundamental difference between being present in a market and belonging to it. Belonging is not a branding exercise. It is the result of consistent signals: local decision-making power, credible local leadership, long-term commitment and respect for local norms.

Companies that remain permanently “foreign” rarely achieve their full potential in a market, no matter how strong their product is. Those that invest in legitimacy early often find that doors open faster, partnerships deepen more naturally, and resilience increases when conditions change. Local legitimacy is not something you buy. It is something you build.

5) The fifth pillar is global orchestration

None of the above implies fragmentation for its own sake. A Local-first global strategy only works if it is supported by strong global orchestration. Learning must circulate. Insights must compound. Strategic intent must remain clear. What changes is not the existence of a center, but its role.

Instead of acting as a command-and-control hub, the global layer becomes an orchestrator of intelligence, coherence and leverage. It ensures that local strategies are aligned without being identical, and that the organization learns faster as it expands rather than slower.

Growth without illusion

Taken together, these pillars form a system. Not a rigid framework, but a way of thinking and operating that replaces anxiety with clarity. Leaders stop asking whether international expansion is still worth it. They start asking how to do it properly.

Frameworks are useful, but they do not substitute for pattern recognition. Knowing which signals to trust, which tensions to resolve locally and which to escalate, when to push and when to pause, is not something you derive from first principles alone. It is learned through exposure, mistakes, course corrections and success across very different environments.

For founders and scale-up leaders, especially in Europe, this is often the missing piece. The ambition is there. The product is solid. The capital is available. What is lacking is not intelligence or energy, but a guide who knows how international growth actually unfolds when theory meets reality.

The end of the flat world narrative creates a natural selection effect. Those who continue to rely on generic playbooks will experience internationalization as a sequence of surprises and disappointments. Those who embrace a local-first approach will find that growth becomes more predictable, more robust and ultimately more scalable.

This is not about slowing down. It is about choosing the right form of speed. The speed that comes from understanding rather than assumption. From legitimacy rather than projection. From alignment rather than force.

When international expansion is approached this way, it stops feeling like a leap into the unknown. It becomes a disciplined process of building power, market by market, without losing coherence or identity. That is how global companies are built in a re-fragmented world.

Not by flattening differences, but by working with them intelligently.